Throughout the elementary years, we informally assess a child’s reading ability by having them read out loud. As the child reads, we can listen for a number of indicators. For example:

Throughout the elementary years, we informally assess a child’s reading ability by having them read out loud. As the child reads, we can listen for a number of indicators. For example:

- Does the child mispronounce specific letter combinations, like “au” or controlled-r sounds?

- Do they struggle to pronounce multi-syllabic words?

- Do they skip words in a sentence?

- Do they pause at the end of a sentence?

- Do they speak with inflection and emotion to help convey meaning from the text?

The interesting thing about oral reading is that it requires an extra layer of effort from the brain than silent reading. When reading orally, a child scans letters and words in a sentence before sending it over to the part of the brain that translates it into sounds. Next, the motor control system must initiate action so the mouth can begin to make the sounds that form the words. All this happens while the oral reader also processes the words for meaning so the child can comprehend the text.

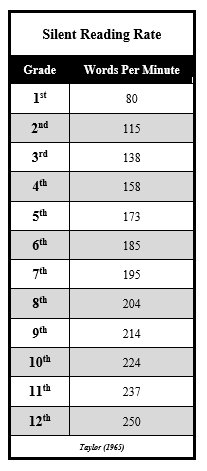

It comes as no surprise that average oral reading rates are lower than silent reading rates at the same grade level.

Despite the extra cognitive load that comes with oral reading, it’s an important part of reading instruction. While listening for reading miscues, we can also check to see if a child self-corrects any or all of their reading errors. Children who fail to recognize they are miscuing words within a text will have different remediation needs than children who recognizing they’re making mistakes but have a hard time accessing the correct information they’ve already learned.

Just as importantly, when a child reads out loud, we can watch to see if they pause to self-check their own understanding of the text. Some children may be excellent word decoders and not make any miscues when they read, but if they race to read all the words on the page without actually taking in what each word means and how they’re linked together into larger ideas, their comprehension will suffer.

Last modified on September 28, 2019